career

Internationally-renowned violinist Jacques Israelievitch enjoyed a varied and richly rewarding career as concertmaster, soloist, chamber musician, teacher, and conductor. As one of North America's most respected performing artists, he appeared regularly throughout North America, Europe, and Asia.

Born in France, Mr. Israelievitch made his solo debut on French National Radio at the age of 11. At 16, he graduated from the Paris Conservatory with three first prizes, and was subsequently a prizewinner at the International Paganini Competition. He studied with such esteemed teachers as Henryk Szeryng, Janos Starker, William Primrose and ultimately, Josef Gingold, for whom he later served as Teaching Assistant at Indiana University.

Appearing frequently with orchestras around the world, Mr. Israelievitch’s career included collaborations with such conductors as Sir Georg Solti, Carlo Maria Giulini, Leonard Slatkin, Raymond Leppard, Sir Andrew Davis, Günther Herbig, Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Stéfane Denève, Thomas Dausgaard, and Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos, among others. He performed as soloist with many orchestras, including the Chicago Symphony, Saint Louis Symphony, Toronto Symphony, Edmonton Symphony, Chautauqua Symphony, Buffalo Philharmonic, CBC Radio Orchestra, Chamber Orchestra of Lithuania, and the China National Symphony Orchestra.

At age 23, Mr. Israelievitch was appointed by Sir Georg Solti as Assistant Concertmaster of the renowned Chicago Symphony Orchestra, thus making him the youngest musician in the orchestra. In 1978, after six seasons in Chicago, he became Concertmaster of the Saint Louis Symphony, a position he held for ten years.

Following his tenure in Saint Louis, from 1988 to 2008 Mr. Israelievitch served as Concertmaster of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra (TSO)—the longest tenure for that position in the ensemble’s history. His tenures with both the Saint Louis and Toronto Symphony Orchestras were highlighted by annual appearances as soloist and conductor, and his entire Concertmaster career is featured in Anne Mischakoff Heiles's 2008 book, America's Concertmasters.

A lifelong advocate for contemporary music, Mr. Israelievitch premiered and recorded many new works, including R. Murray Schafer’s The Darkly Splendid Earth: The Lonely Traveler, which was commissioned for him by the TSO and subsequently recorded for CBC Records. In 2004, he performed Jeffrey Ryan’s violin concerto, The Chalice of Becoming, with conductor Bramwell Tovey and the Vancouver Symphony. This work, also commissioned for him, was premiered by Mr. Israelievitch and the TSO.

Beyond his solo and orchestral activity, Mr. Israelievitch was an accomplished and devoted chamber musician, performing with such distinguished artists as Emanuel Ax, Yefim Bronfman and Yo-Yo Ma. He was the violinist of the New Arts Trio, founder of the Toronto Symphony Quartet, and recorded with pianists John Greer, Robert Kortgaard, Christina Petrowska Quilico, Stéphane Lemelin, Kanae Matsumoto, and Stephanie Sebastian. In addition to regular performances on the violin, in 2008 he began concertizing on the viola.

Teaching was another constant in Mr. Israelievitch’s career. From 2008 to 2015, he served as a full-time violin and viola professor on the Fine Arts faculty at Toronto’s York University, while also teaching at the University of Toronto and Royal Conservatory of Music. For sixteen summers, he was on the violin faculty at the Chautauqua Institution in Western New York, mentoring an international class of violinists, coaching chamber music groups, and serving as Chair of the string department. Guest master classes over the years brought him to Florida’s New World Symphony, the Manhattan School of Music, Eastman School of Music, Cleveland Institute of Music, Oberlin College, the University of Michigan, Meadowmount School of Music, McGill University, Conservatoire de Montréal, Orford Music Festival, the Central Conservatory in Beijing, and the Toho School of Music in Tokyo, among other institutions.

As conductor, Mr. Israelievitch led the Saint Louis Symphony, Toronto Symphony, Buffalo Philharmonic, Windsor Symphony, Orchestre du Conservatoire National Superieur de Paris, and other ensembles in North America, France, and Japan. He was Founder and Music Director of the Chicago Pops Orchestra, the Pro Musica Society of Chicago, and the Koffler Chamber Orchestra at the Koffler Centre of the Arts in Toronto.

Mr. Israelievitch’s discography includes the Juno Award-nominated Suite Hebraique; Bruch's Violin Concerto No. 2 with the Chamber Orchestra of Lithuania; Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, K. 364, with violist Steven Dann and the CBC Radio Orchestra; Beethoven’s Romances with the TSO; an all-French album with the Mirage Quintet; two recordings with the New Arts Trio; French Violin Sonatas with pianist Kanae Matsumoto; Fancies and Interludes with pianist Christina Petrowska Quilico; and the albums Suite Française, Suite Enfantine, Suite Fantaisie, Solo Suite, and Hammer and Bow, the last-named with his son, percussionist Michael Israelievitch.

Mr. Israelievitch is the featured violin soloist in Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake ballet conducted by Leonard Slatkin on RCA Red Seal, and can be heard in orchestral recordings for Deutsche Grammophon, EMI, Decca, Sony/BMG, Telarc, and Finlandia.

In 2006, Mr. Israelievitch released the first-ever complete recording of Kreutzer’s 42 studies for solo violin -- a project that has garnered worldwide recognition.

Jacques Israelievitch relished all kinds of musical activity. One of his madcap ventures was the Marathon Concert. This began in March 1985 when he organized dozens of musicians to play a 12-hour series of music by J.S. Bach to celebrate the composer’s 300th birthday. His own performance marathons began in Canada, often constituting “first-evers”. These included a 6-hour performance of the 10 Beethoven violin and piano sonatas (a feat he essayed twice); a 4-hour performance of all Brahms’s works both for violin and for viola; and, shortly before his death, an almost 8-hour performance of all 28 Mozart Sonatas for violin and piano. Another such ‘marathon’ concert was his final concerto performance as Concertmaster of the TSO, when he performed three concerti on one program: Bach’s Double Concerto for Two Violins with longtime stand-partner Mark Skazinetsky; a world-premiere Double Concerto by Kelly-Marie Murphy, joined by his percussionist son, Michael; and Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto.

In 1995, on behalf of the Institute for International Affairs, B’nai Brith presented Jacques Israelievitch with a human rights award in recognition of his outstanding moral leadership. That same year, he was inducted by the French government into the Order of Arts and Letters and in 2004 was promoted to the status of Officer. In 2015, he was appointed to the Order of Canada, his country’s highest civilian honour. He was also the recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award, presented to him by the Toronto Musicians’ Association in recognition of his distinguished contribution to the performing arts in Canada.

Jacques Israelievitch passed away on September 5, 2015. Despite a cancer diagnosis six months earlier, he was determined to complete one final project: a multi-disc set of the complete Mozart Sonatas and Variations with pianist Christina Petrowska Quilico. The first volume was released in Spring 2016, and Volume Two in Fall 2017. The remaining discs will be released in the coming years.

Ellen Bialystok, Stephen Cera, Michael Israelievitch

Header photo by Barry Elz

Hand portrait by Gabrielle Israelievitch

a bit of history...

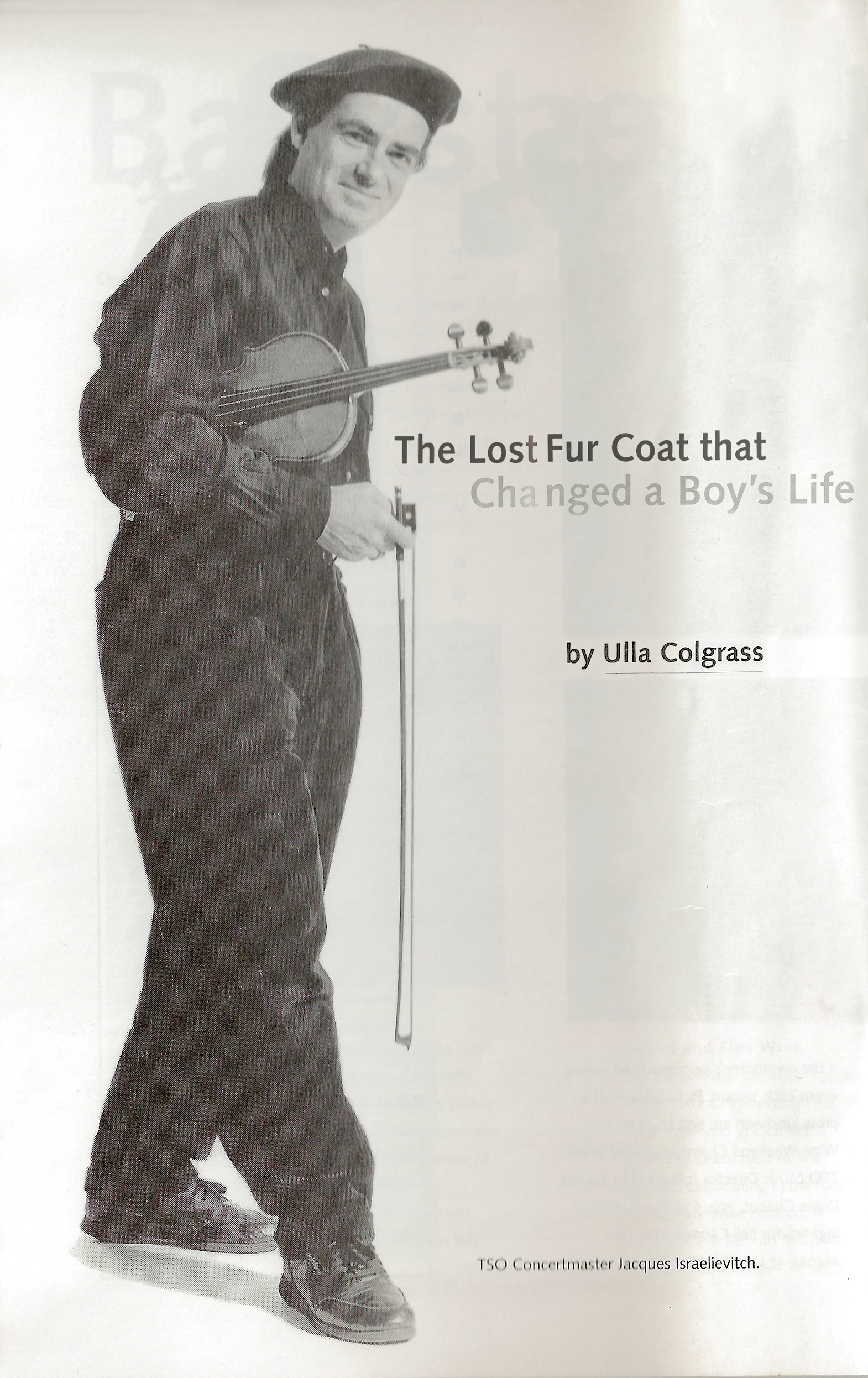

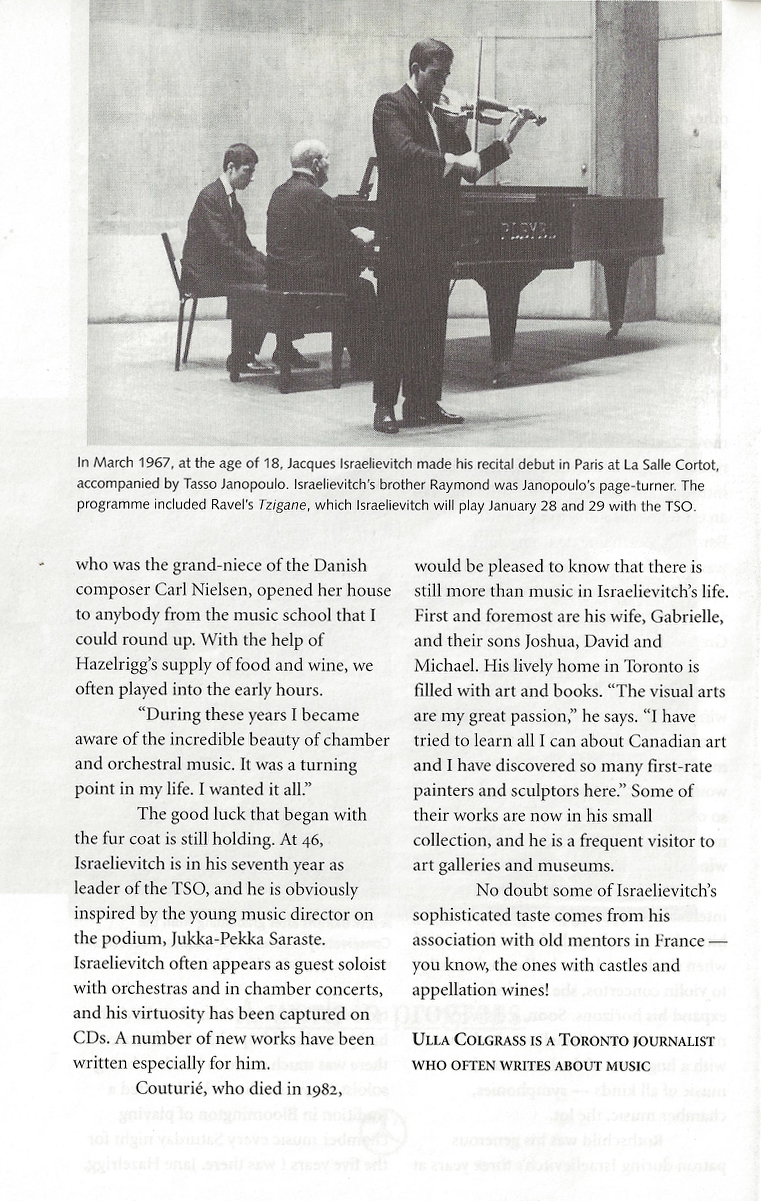

TSO House Program January 1995

Cover photo by Cylla Von Tiedemann

When I met Jacques, the first question he posed after asking my name was: “Are you Jewish?” Even after knowing him for thirty-plus years, I couldn’t say exactly what the significance was of my answer to him... or why he even asked. Maybe simply to see if we were part of the same clan. He was neither a practicing nor a particularly knowledgeable Jew, but he was very connected to “being Jewish.” This was largely because of what it meant to be a Jew in France when he was a child.

His family of origin had been devastated by anti-semitism for at least the two generations which I know about. His father, Isidore (1906-1991), a soldier during the war, was imprisoned for five years in a labour camp. Upon returning to Paris, he discovered his parents had been deported to Auschwitz, along with many extended family members. Isidore was left with a nagging notion that his (first) wife had betrayed them. The woman who was to become Jacques’ mother, Simone (b. 1927), survived World War II as a teen, hiding in the outskirts of Paris with her single, illiterate Romanian mother who traded her body to ensure their safety. Simone vividly recalls her fear of venturing out to get food, covering the Star of David with her purse, then turning around and returning home – shaking and starving – after noticing a soldier nearby. In the last weeks of the war, Jacob (after whom Jacques was named), the only brother of Jacques’ father and a member of the French Resistance, was denounced and shot.

By the time the couple came together in the late-1940s, they brought with them all the unspoken war trauma they each carried. They proceeded to do what many did, to ‘re-populate’ the Jewish world by having children. There turned out to be five – of whom Jacques was the eldest -- and none could help being affected by their parents’ experiences. Jewish identity was in their history, their name (which Isidore refused to change), and in the ways in which they were treated by others. This did not necessarily extend to their practise of Judaism, though Jacques and his next brother, Raymond - who later changed his name to Reouven - became B’nai Mitzvot in a joint service at one point. (Neither of them learned Hebrew at this time but both were gifted in music and memorizing.) Raymond later became a Lubovitcher, the only practicing Jew in the family. He had nine children, who in turn spawned 25 children, all of whom remain Lubovitcher.

Prior to the war, Isidore’s family had several women’s clothing stores for which Isidore had worked as the buyer. After the war, the stores and the family were mostly gone. Although he attempted to salvage something of the business, it had been his father who ran things, so Isidore struggled on his own. When he and Simone got together, they tried unsuccessfully to resurrect the Paris stores. Although the family had been from Paris (Jacques was born in Cannes during a holiday), they moved to Le Mans to run the sole profitable shop that was being managed by Isidore’s first wife. I don’t know how this was arranged, or what happened to her, only that Simone worked there designing the store-front window displays. Apparently she was prone to ‘spells’ and took to bed at every slight. Isidore was compelled to invite his mother-in- law to come from Paris to live with them in order to look after the children and to cook. I don’t have a sense of how her infirmities affected the running of the store as much as they affected the family, but the store’s success was relatively short-lived. It was not, however, for the expected reasons.

The name of the street on which the family lived in Le Mans was Rue des Victimes de Nazisme. Ironically, the victim-hood of these particular residents didn’t end with the war. Jacques talked about having been continuously taunted as a “sale juif’ (“dirty Jew”) at school, which sparked some fights. Even more chilling was that within five years,the family was driven out of business and out of Le Mans itself by the wave of anti-Semitic rumors that swept through small towns in France in the mid-Fifties, e.g., accusations that Jewish shopkeepers were abducting women and selling them into prostitution in Africa. No amount of intercession with either the police or the church could make a difference, and the family was forced to leave and to re-invent themselves.

They farmed out the three older children to other homes during their transition back to Paris (1960), where they eventually opened a convenience store behind which they all lived—eight people, a dog, and a cat—in two rooms with no private bathroom. The older kids helped out in the shop after school and on weekends. Ultimately, however, the store failed when a larger grocery store opened nearby. So they closed their shop, moved to another apartment, and Jacques’ father began driving a taxi. This is what Isidore was doing when Jacques moved to the U.S. at age 17 for his university studies.

Within the family, Jacques had it best. During the travails of his childhood, he had a single focus from the age of eight: his violin. By the time he turned ten, he had benefactors. When the three older children were dispersed during the family’s transition back to Paris, Jacques went to the Jewish orphanage sponsored by his sponsor, the Baronness of Rothschild. The other two went to strangers’ homes. So he was plucked out of challenging situations by the combination of his gift, his grit, and his good fortune. This had a double effect: he led an easier life and was able to escape to some extent the ongoing family turbulence. Yet it also led him to feel responsible for all of them. And throughout his life, he remained keenly sensitive to issues of anti-Semitism.

Jacques was given to bold stands and on one occasion his position drew a lot of attention. That was when Jörg Haider, a known Nazi sympathizer, was freely elected in Austria and became part of that country’s governing coalition... at just the time the Toronto Symphony Orchestra was scheduled to play in Vienna (February 2000). Jacques, the TSO’s concertmaster, at first refused to join the orchestra’s tour, and his forthright stand created a controversy.

Ultimately compromises were reached. The orchestra did go to Vienna, with Jacques, but the printed program included a position statement (attached in translation below*) from conductor Jukka-Pekka Saraste on behalf of the orchestra. They also played an unscheduled piece, Meditations, from Leonard Bernstein’s Mass. During this trip Jacques met with the late Simon Wiesenthal, renowned Holocaust survivor, Nazi hunter, and writer. In my personal favourite of all his public acknowledgments, B’nai Brith honoured Jacques for his moral courage.

Jacques was a unifier—of art forms and artists, and of people from diverse circumstances. He became so happy conducting different orchestras, and was especially proud to spend one summer in the early 90s conducting the Orchestra of Youth from the Mediterranean where Arabs and Jews, Serbs and Croats were sharing music stands, meals, and friendships. He only saw the budding musician in each student, loving them all whether their gifts were large or not so large. He always found something to nurture and bring to life. What he said of composers was also true of his students: whichever one he was teaching or playing at the moment was his favourite.

Although he generally avoided organized religion, after being invited to play Kol Nidre at a friend's Yom Kippur service, Jacques continued to make this an annual offering (i.e., without fee.) He also played it on several occasions in the homes of very ill friends. There was one Yom Kippur when he was unable to play, so he asked one of his students, Amir Safavi, if he would play in his stead – which Amir did. Amir is not Jewish, so his gesture was particularly moving.

Jacques played over the phone and (in later years) over Skype to friends who were dying. He played at the death-beds of friends, including Molly Sverdrup, who had paid off the huge mortgage for Jacques’ violin as our wedding gift. He played Kaddish at the funerals of other friends. Less than a year before his own diagnosis, he played at my father’s service. As Jacques approached the end of life, I asked him if he would like someone to play Kaddish at his funeral. He said 'yes' and requested Amir, remembering how beautifully Amir had rendered the Kol Nidre. Jacques’ presence was palpable during Amir’s loving tribute to his teacher.

There is something about playing music that gives one direct access to spirit. Over the years, when Jacques’ grandmother, then his father, then his sister, then his brother died...he played for them, and to them. He did this both in the privacy and solitude of his own studio and in tributes on concert stages. It was his distinctive voice – and it was a Jewish voice.

* On behalf of all the musicians of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra I can assure you how much we look forward to the concerts at the Vienna Music Society. Nevertheless, the decision to accept an invitation for a guest appearance in Austria was not an easy one for us.

We are very disturbed by the widespread extremism in speech and ideology in Europe today. Many of our musicians are descendants of those who so recently suffered from racial intolerance and religious persecution. That makes the trip to Vienna in these times particularly difficult.

To express our dismay over the political situation in Austria we begin our concerts with the Meditation No. 1 from Leonard Bernstein’s “Mass.” Bernstein was an artist who fought tirelessly against intolerance and discrimination, and at the same time loved Vienna and its people. Canada is a young country with a commitment to multiculturalism. With the three concerts in Vienna the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, along with its youth allies itself with all those Austrian artists who commit themselves, as we do, to humanitarianism and tolerance.

Translation: Alice Pitt, Shaya Izenberg

being jewish

This is a snapshot of the family tomb located in Bagneux (Paris), taken around 1991. Jacques' sister Evelyne (d. 1995) and his brother Edmond (d. 2016), were also buried here. His brother Raymond/Reouven (d. 2014) was buried in Jerusalem. Jacques was buried near Toronto in Pardes Shalom.